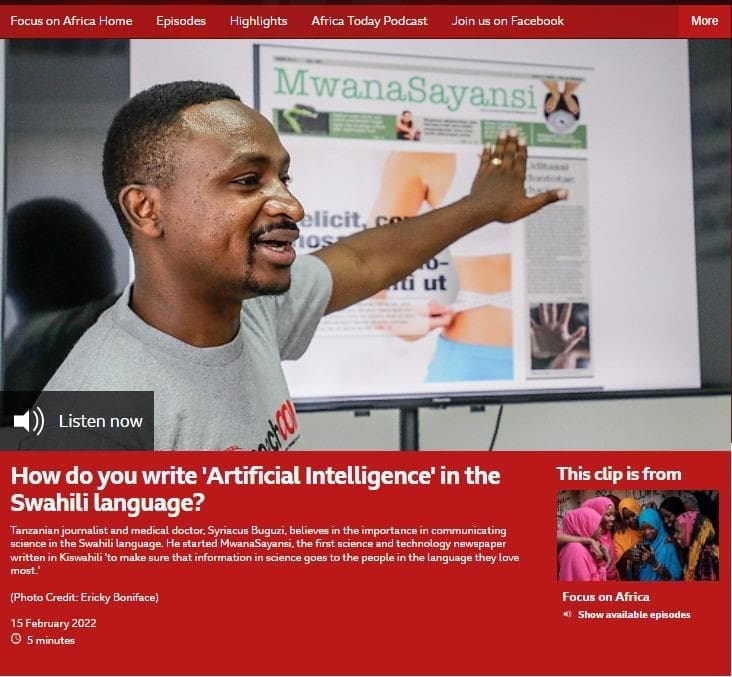

Image: Tanzanian journalist and medical doctor, Syriacus Buguzi. ©BBC

02/03/22

Blog

Doctor turned science journalist launches first newspaper of its kind

Speed read

- Tanzanian science journalist and medical doctor has launched the first Swahili language science and technology newspaper.

Meet Syriacus Buguzi – a pioneering medical doctor turned science journalist from Tanzania. He is making the headlines after spawning the first Swahili language science and technology newspaper, MwanaSayansi.

Dr Buguzi is a former health correspondent with The African and The Citizen. He is a seasoned contributor to SciDev.Net having covered a range of stories including a special investigation on COVID-19 as part of a SciDev.Net Investigates series.

He is also a David Astor Journalism Award winner. He has even tasted life as a journalist for the UK national media outlets The Independent, The Observer and The Guardian. Syriacus is also a recent Masters’ Degree graduate from the University of Sheffield after studying Science Communication.

After being spurred on by undertaking two free training courses provided by SciDev.Net – the Script Science Communication Skills for Journalists and Media Skills for Scientists, Dr Buguzi believes MwanaSayansi could be his greatest achievement yet in bringing valuable science news and analysis to Tanzanian people in the language they love the most.

Fresh from a BBC World Service interview ‘How do you write ‘Artificial Intelligence’ in the Swahili language?, Dr Buguzi tells CABI, SciDev.Net’s parent organisation, how SciDev.Net and Script has helped him bring MwanaSayansi to fruition and how the free training can help other budding journalists and newspaper editors thrive in their field.

Q: What did you want to be when you were growing up?

Dr Buguzi: Like what most kids do, I think I grew up dreaming of becoming one of those people who are often praised for doing marvellous things, especially in science. I admired medical doctors, mostly. That’s probably why I studied medicine later when I joined university. But while growing up, I was always curious why my father liked listening to radio almost all the time. Then, that curiosity grew into something else. By 1999, when I was completing primary school, I was already admiring radio presenters. Somewhere in between, I started wanting to be like the presenters.

Q: What challenges did you face early on in your life and career?

Dr Buguzi: At the age of 13, I was transferred to a boarding primary school in neighbouring Uganda where I had to cope with all teachings in English, and learning a new local language. In Tanzania, everything had been taught in Kiswahili but most of the time we spoke our vernacular, Lunyambo. The shift to all-English teachings and interactions in Luganda made me lag behind academically. But later I made it. On my return to Tanzania for secondary education, I realised I was forgetting Kiswahili. And the learning cycle continued. But all was like a blessing in disguise.

Q: Who or what has inspired you the most?

Dr Buguzi: At various stages in my life, I have been inspired by many people, mostly my father who is an agricultural officer-turned politician. He discouraged me from pursuing arts subjects in high school. I had told him I wanted to study to become a journalist but he insisted I should take Physics, Chemistry, and Biology. He told me, “Go study science subjects, if you still want to write, you will write science.” At that stage, it sounded impossible to connect science with journalism. But 18 years later, here I am, a science journalist.

Q: How did you go from being a medical doctor to a science journalist – that’s quite a shift in career?

Dr Buguzi: I rarely view this as a shift but a process to create a unique career. For many years, even when still in medical school, I was trying to link medicine and journalism, inspired by the passion for journalism. All my extra-curricular activities while in medical school centred on media. I was Editor-in-Chief of Dar es Salaam Medical Students’ Journal at university. Over the years, I realised there was an opportunity to blend medicine and journalism to nurture a new career. By the time I completed internship in 2014 as a doctor that desire hadn’t ended.

Q: How important is science journalism in learning more about the world around us and changing it for the better?

Dr Buguzi: Very important. Science journalism is a unique professional niche that makes one try to find meaning in scientific processes or discoveries. For instance, things that people would take for granted, such as the oxygen we breathe in and the carbon dioxide we breathe out — and how these gases can determine our co-existence with the green plants we see around us, and the food that these plants make through photosynthesis, for us to eat. A science journalist can decipher these complex human-plant interactions and tell a story on agricultural development, in a way that society engages with it and learns something.

Q: How did the Script training courses help you in your career – particularly in creating the pioneering MwanaSayansi?

Dr Buguzi: I was one of the first graduates of science communication skills for journalists. The course sparked my interest to pursue sci-com skills at a higher level and that’s how I applied to do a Masters in Science Communication at the University of Sheffield. While doing my masters, I strengthened my long-held dream of starting the Swahili science newspaper; to serve majority of Tanzanians who love speaking their language. To get the writers of the newspaper on board, I made it a requirement for them to first enrol for Script Training before joining our team. It’s helping us write science better.

Q: What do you think others can get out of the Script science communication training available?

Dr Buguzi: The training is an eye-opener. And I would recommend it for everyone hoping to start a career in science communication. I always ask my science journalism mentees what they have learnt from the free science communication skills for journalists’ course, and the common answer has been “How to humanise science.” There are plenty and interesting examples to learn from in each of the topics taught. The training could also give you a starting point to further pursue science communication projects and science journalism grants.

Q: How important is it for publications like MwanaSayansi to speak in the language of its audience?

Dr Buguzi: First of all, MwanaSayansi is designed for the Swahili-speaking audience in Tanzania. Predominantly, Swahili is the language of the media in Tanzania. For a long time, this audience has enjoyed specialised news coverage in sports, entertainment and politics through Swahili media outlets but there has been no specialised media for science. Since MwanaSayansi focusses on stories with a science research background, this also means that most scientists in Tanzania whose journal papers are often published in English, can now have more access to end-users of the science knowledge. Our newspaper is helping overcome the linguistic barrier in science.

Q: What do you think the future holds for science journalism in Tanzania?

Dr Buguzi: There is some progress, although I still see a sense in which the local media doesn’t give emphasis to science stories. But as time goes, I see growing interest among journalists — but also growing interest among scientists who are trying to venture into this journalism genre. The future doesn’t yet look so bright but I can see some initiatives going on.

Q: Finally, there are some famous scientists who have become media celebrities such as Professor Brian Cox in the UK. What role can such figures play and do you think you’ll ever practice as a doctor again or combine both medical and journalistic careers in a similar way?

Dr Buguzi: I view media celebrities like Professor Brian Cox as catalysts in science communication; because they demonstrate a skill that most scientists should emulate, and they are an inspiration to many. As for me, I tend not to imagine myself as “a doctor in the newsroom” or a scientist in the newsroom. From 2014, when I made the decision to become a full-time journalist, the long-term plan was to stick to journalism. The medicine that I studied and practised for a while, remains my background profession and an added advantage in the journalism niche that I am pursuing.

Dr Buguzi has been interviewed by

BBC World Service’s Focus on Africa

series – explaining why he felt the need

to start MwanaSayansi, the first science

and technology newspaper written

in Kiswahili. You can listen by clicking

the image above or here.